Many of us are familiar with the first-person shooter (FPS) creation myth—that it materialized fully formed in the minds of id Software founders John Carmack and John Romero shortly before they developed Wolfenstein 3D. Afterward, it was pushed forward only by id until Valve's Half-Life came along.

But the reality behind FPS evolution is messier. Innovations came from multiple sources and often took years to catch on. Even Wolfenstein 3D had numerous predecessors within and without id. And like the genres we've previously explored—a list including city builders, graphic adventures, kart histories, and simulation games—there have been many high and low points throughout this long, violent, gory history.

Minus '90s cult favorite Descent (because I personally consider it a flight combat shooter), these are the shooters that pushed the genre forward or held it back. Many of us encountered at least one that truly spoke to us, but together, these titles made it cool to shoot pixel-rendered dudes, dudettes, mutants, and weird alien creatures in the face.

-

Maze Wars+

-

Faceball 2000

-

MIDI Maze

Pre-history

In the beginning, there was Maze. Later remade for several 1980s and early '90s machines under numerous variant titles such as Maze War, Maze Wars+, Super Maze Wars (the version I played to death on a Mac), Bus'd Out, Faceball 2000, and MIDI Maze, this first version of Maze was programmed on an Imlac PDS-4 minicomputer in 1973. It was a two-player 3D maze game coded by three high schoolers—Greg Thompson, Steve Colley, and Howard Palmer. They completed the would-be masterpiece during a work/study program at NASA's Ames Research Center. Thompson and Infocom (the text adventure company) co-founder Dave Lebling then carried on the work at MIT the following year.

They progressively added more features, and soon Maze became what we would now call a first-person shooter. Besides shooting each other, players could peek around corners and check a map to see where they were in the maze, and opponents looked smaller or larger according to distance. Perhaps coolest of all, other people could watch the eight-player action unfold on a Sutherland LDS-1 graphics display computer—one of the earliest cases of gaming as a spectator sport.

Maze was played across a network (via a PDP-10 mainframe) within MIT and over the ARPANET—an early version of the Internet—between MIT and Stanford. Legend has it that the game got so popular it was banned from ARPANET because it chewed through too much data.

Jim Bowery's 32-player, 3D networked, first-person perspective space shooter Spasim—a kind of forebear to space combat sims Star Wars: X-Wing and Elite—got its first release on the PLATO computer around this time as well, effectively making Maze and Spasim joint ancestors of the FPS genre. However, they weren't the only pre-id Software games to provide real-time, first-person perspective shooting.

-

Spectre.

-

The Colony.

-

Gun Buster.

Pseudo-3D arcade first-person tank shooter Battlezone hit in 1980, with wireframe vector graphics that not only gave it a novel and iconic look but also let it run super fast. Battlezone got cloned on every platform known to man in the 1980s and early '90s, but none was worthy of much note besides Spectre (1991)—a networkable Macintosh game that asked players to capture flags as quickly as possible while driving around an abstract, futuristic map blasting (or on higher levels, fleeing) enemy tanks.

The Mac also hosted another important progenitor to the FPS genre: The Colony (1988). Part horror puzzler and part shooter, The Colony was a terrible game—you could die in several different ways without warning or explanation just in the supposedly "safe" opening section (and it just got more sadistic from there). But in terms of its technical achievements, The Colony was remarkable. It presented a huge, sprawling, detailed (underground) black-and-white, mostly wireframe 3D world with real-time graphics rendering and 256 degrees of freedom in where you could look (using the mouse, no less—years before it became a genre standard). The Colony looked stunning, like a vision of the future. But its fame extended little beyond the Macintosh faithful.

No less obscure than The Colony and just as significant, Taito's Gun Buster (1992) was the first—and one of the only—light gun games to go off rails. Rather than giving you control only over shooting, as was the norm, it gave you a joystick for forward/backward and strafing movements and mapped turning to the light gun's aiming reticule. It had cooperative and head-to-head modes for one to four players, breakable glass in its first level, and graphics that PC shooters wouldn't match for another few years. Sadly its distribution, and hence its impact, was sorely limited.

Mecha-Hitler

Coding wizard John Carmack wanted to take the ponderous first-person 3D action of flight simulators and make it fast like an arcade game. He had just one problem: home computers at the time—this is 1990—were slow. In order to make a fast-paced, 3D first-person action game, he had to take some shortcuts. His solution was to use a technique called raycasting, which involves sending invisible rays out from the player's position in the direction they're facing and then performing simple calculations to determine where and at what height to draw walls.

Hovertank (1991) turned out not to be the most impressive game, with ugly, solid-colored walls, a black ceiling, and gray floors coupled with repetitive shooting of uninspired enemies. Still, it was a start.

Carmack soon refined his raycasting engine and developed a mapping system to put textures on the walls—a system that he came up with after hearing about the 3D engine for in-development, first-person role-playing game Ultima Underworld. Unlike Underworld, however, Catacomb 3-D (1991) only put textures on the walls. The ceilings and floors were still just solid blocks of color. It also introduced a cartoon head that showed the health of your hero, but the game was too graphically limited (3D engine aside) to make a big impression.

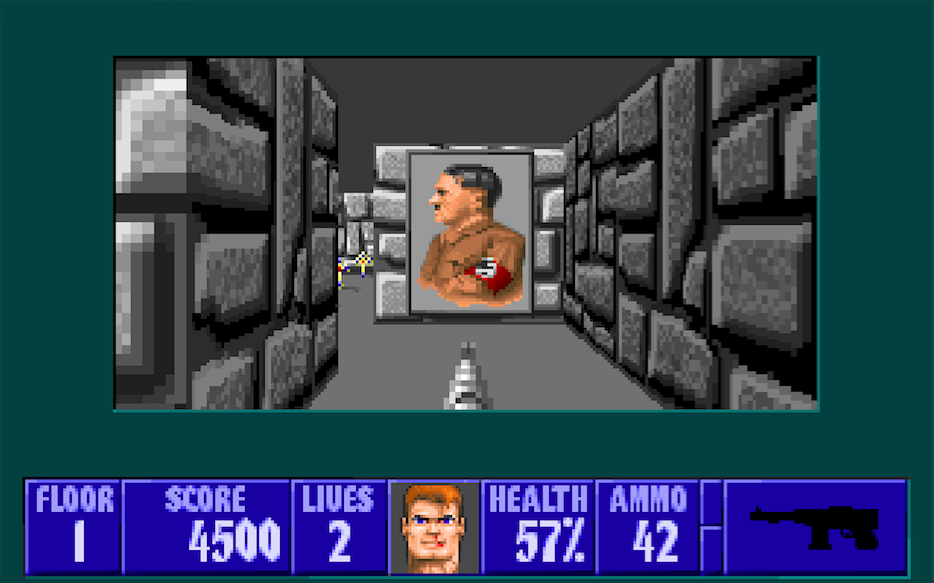

That wasn't the case with id's next attempt, Wolfenstein 3D (1992). Here, id finally came into its own. Carmack figured out some tricks to speed up his rendering engine, while designers John Romero and Tom Hall crafted maze-like maps with loads of secret rooms, and artist Adrian Carmack (no relation to John) hand-drew the 256-color object/character sprites—a big step up visually from its earlier 16-color EGA titles.

Wolfenstein 3D's popularity was not merely a product of its technical achievements, though. The episodic shareware shooter ditched the fantasy stylings of Catacomb for good ol' Nazi killing. The simple-yet-ridiculous setup of spy William "BJ" Blazkowicz deciding to singlehandedly topple the Nazi regime—and with it their secret army of undead mutants—made for easy motivation.

Word got around fast that not only was Wolfenstein 3D full of cool Easter eggs and hidden rooms, but come episode three, you could kill Hitler. Or rather Mecha-Hitler—the crazed homicidal tyrant donned a huge robot suit equipped with four chainguns and a creepy, uncanny ability to always be looking right at you. If you managed to actually kill him, he didn't just keel over quietly; he exploded into a disgusting but oh-so-satisfying pile of blood and guts. You even got to watch his final moments again in slow motion on the game's gory, controversial Death Cam.

This dedication to over-the-top graphic violence landed id in hot water repeatedly through the '90s—particularly with German censors and Nintendo's strict no-blood policy on the Super Nintendo. The game maker also felt the heat from religious groups and eventually, in the wake of the Columbine High School massacre in 1999, with the broader public. Still, this work was critical to the edgy, raw, arcade-y image that id fostered in its march to world domination. Other developers simply raced to play catch up.

reader comments

266